Clayton Christensen, in 2003’s The Innovator’s Solution, explained how the natural course of industries was from interdependent architectures to modular ones:

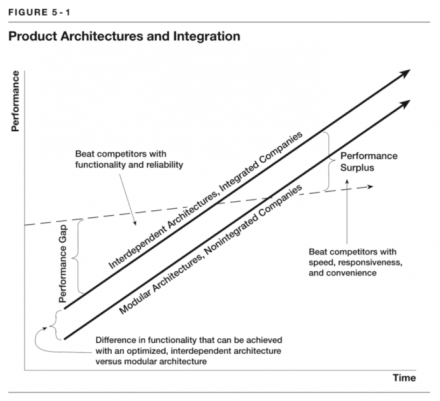

Customers will not buy your product unless it solves an important problem for them. But what constitutes a “solution” differs across the two circumstances in Figure 5-1: whether products are not good enough or are more than good enough. The advantage, we have found, goes to integration when products are not good enough, and to outsourcing — or specialization and dis-integration when products are more than good enough.

The left side of Figure 5-1 indicates that when there is a performance gap — when product functionality and reliability are not yet good enough to address the needs of customers in a given tier of the market — companies must compete by making the best possible products. In the race to do this, firms that build their products around proprietary, interdependent architectures enjoy an important competitive advantage against competitors whose product architectures are modular, because the standardization inherent in modularity takes too many degrees of design freedom away from engineers, and they cannot not optimize performance.

The pressure of competing along this new trajectory of improvement forces a gradual evolution in product architecture, as depicted in Figure 5-1 — away from the interdependent, proprietary architectures that had the advantage in the not-good-enough era toward modular designs in the era of performance surplus. Modular architectures help companies to compete on the dimensions that matter in the lower-right portions of the disruption diagram. Companies can introduce new products faster because they can upgrade individual subsystems without having to redesign everything. Although standard interfaces invariably force compromises in system performance, firms have the slack to trade away some performance with these customers because functionality is more than good enough.

Modularity has a profound impact on industry structure because it enables independent, nonintegrated organizations to sell, buy, and assemble components and subsystems. Whereas in the interdependent world you had to make all of the key elements of the system in order to make any of them, in a modular world you can prosper by outsourcing or by supplying just one element. Ultimately, the specifications for modular interfaces will coalesce as industry standards. When that happens, companies can mix and match components from best-of-breed suppliers in order to respond conveniently to the specific needs of individual customers.